AI Feels Smarter Because the System Is

A better experience must mean a smarter model. A more helpful response must mean the model is learning. This assumption is natural, but it is also incomplete.

Next month, I’ll be traveling to Texas to speak at the TEEX conference about security and AI. One of the challenges with that topic is not explaining what AI can do, but explaining what it actually is. There is a growing gap between how AI systems feel when we use them and how they truly operate under the hood. Before we can talk about security, risk, or trust, we need a shared baseline understanding of how modern AI systems work and just as importantly, how they do not.

Most discussions about AI start and end with the term “LLM,” or large language model. We compare one product to another, one chat experience to another, or one API to another, and we assume that the difference in quality must be driven primarily by the model itself. A better experience must mean a smarter model. A more helpful response must mean the model is learning. This assumption is natural, but it is also incomplete. An LLM is only one component of a much larger system, and focusing exclusively on the model hides where most real progress is happening.

This misunderstanding becomes obvious when we look at how AI feels during conversation. When you interact with a chat application like ChatGPT, the system clearly appears to know what you said earlier. As the conversation continues, responses feel more relevant, more aligned with your intent, and more informed by past exchanges. In some cases, it even appears to understand patterns across multiple conversations. The experience strongly suggests learning. And yet, during that entire interaction, the underlying language model is not changing at all. It is not updating itself. It is not retaining memory. It is not learning from you in the way people intuitively expect. So what is actually happening? Why does a static model produce an experience that feels dynamic and adaptive? Answering that question is the key to understanding modern AI systems.

The LLM is Frozen

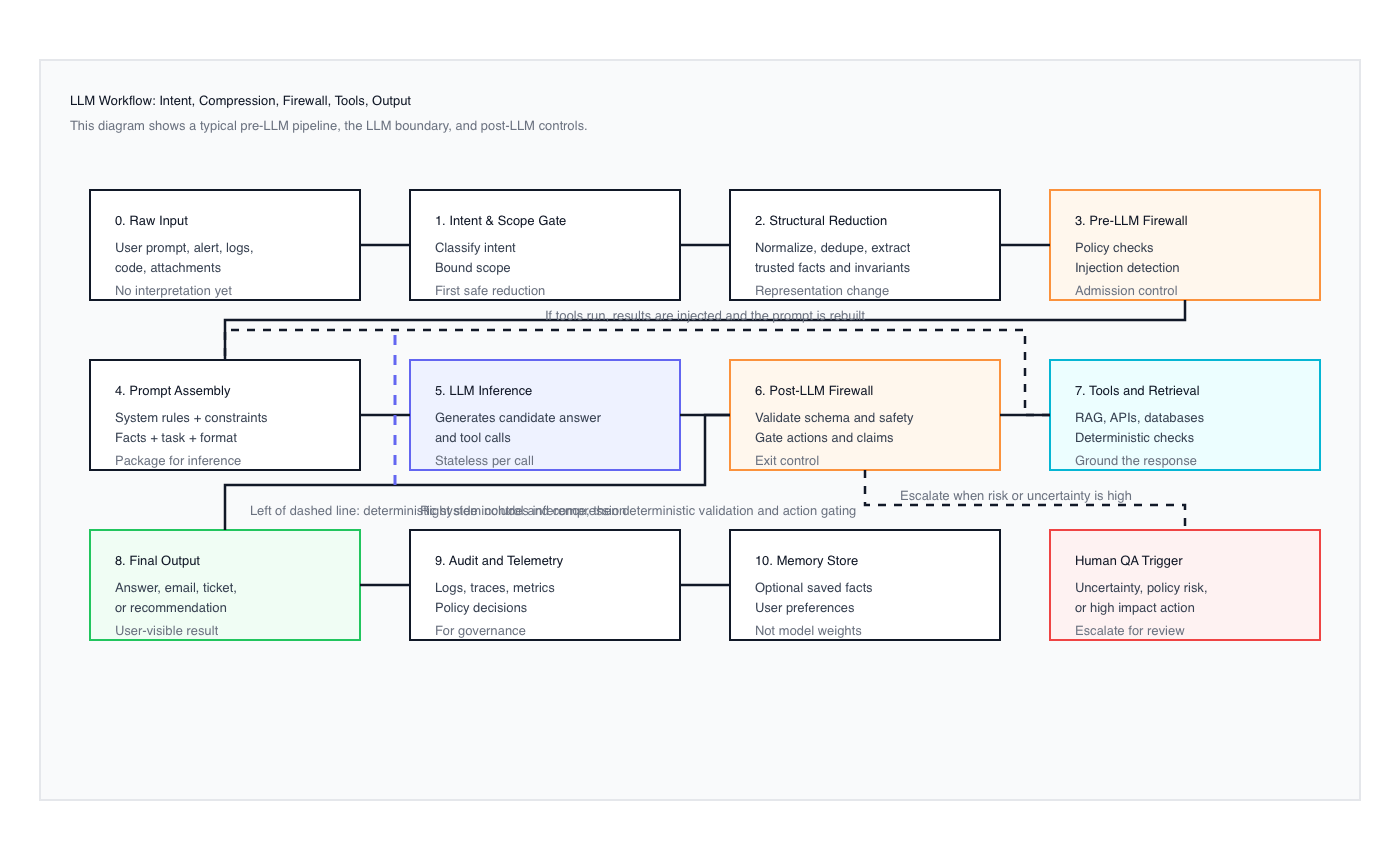

When we talk about an LLM, it’s important to separate the model from the product wrapped around it. The language model itself is static and frozen at inference time. Its weights do not change during a conversation, and it does not retain memory between requests. Each response is generated from scratch based solely on the prompt it receives at that moment. Any sense of continuity comes from the software intercepting your input, modifying the prompt, and resubmitting context along with your latest request. The LLM never sees a “conversation” in the human sense. It sees only a single, assembled prompt and produces a single output. While models are periodically updated, those updates happen offline through training pipelines and reinforcement processes, not through your interactions. Understanding this is critical: the model is not learning from you, and it does not know anything about your past conversations unless that information is explicitly provided again.

A Summary of the Chat is Sent with Each Prompt

If the language model itself is frozen, then the obvious question is what creates the sense of continuity in a chat. The answer is that the chat software is sending far more than just your most recent message. Along with each new prompt, the system re-submits selected portions of the earlier conversation, often in compressed or summarized form. Early in a session, that summary may be relatively detailed. As the conversation grows, the system continually updates and reuses a more compact version, replacing raw history with a condensed representation of what it believes matters. This process gives the model a view of the past without the model ever remembering anything itself. When the prompt is finally submitted, the LLM sees only the current message and the reconstructed summary provided to it. Nothing exists outside that prompt. Continuity, then, is not recall or learning. It is reconstruction, and someone or something has decided what parts of the conversation are preserved and what parts are allowed to disappear.

At some point, the system cannot continue resubmitting the entire raw conversation without exceeding practical limits. Context windows are finite, and raw data grows quickly. To keep the interaction going, the system must reduce what it sends, and that reduction is compression. Compression simply means taking something large and making it smaller while attempting to preserve what matters. There are several ways to do this. Truncation removes older content entirely. Summarization replaces detailed history with a condensed description. Structural reduction changes the form of the data, removing repetition, normalizing patterns, or extracting key elements instead of carrying full text. If a point has been repeated multiple times, it may be collapsed into a single statement. This is where meaningful differences between chat systems begin to appear. How information is compressed has a greater impact on behavior than the language model itself. Compressing source code is fundamentally different from compressing a casual conversation, and systems that treat all input the same inevitably lose important structure. What feels like intelligence is often nothing more than a better decision about what to preserve and how to represent it.

Summary of Summaries Creates Drift

Summarization is unavoidable, but it is also where problems begin to surface. Any summary is inherently lossy. Details are dropped, nuance is flattened, and judgment is applied about what matters most. That judgment may remove repetition, but it can also remove tone, intent, constraints, or subtle qualifiers that were important to the original discussion. Over time, this introduces drift. Each new summary is built not from the full conversation, but from the previous summary plus a small amount of recent context. What emerges is a “summary of a summary,” an increasingly compressed interpretation of the original exchange. As this process repeats, the representation grows weaker and less faithful, even as the conversation feels more productive. This is why long sessions eventually degrade, not because the model is failing, but because the system is no longer operating on the same problem it started with. The effect is similar to the classic message-passing exercise where a sentence changes meaning as it is repeated from person to person. The model is not revisiting the full history. It is reasoning over the latest compressed version, and that version is only as accurate as the compression decisions that produced it.

This problem becomes much more visible when we move from conversation to code. Natural language tolerates approximation. Code does not. Dropping a detail in a casual discussion may slightly change tone or emphasis, but dropping a detail in code can silently break correctness. Code contains long-range dependencies, implicit assumptions, and brittle structure that must remain intact for reasoning to hold. As a result, summarization is far more difficult, and failures show up faster. This is why coding sessions tend to hit limits earlier than conversational ones, not because the models are weaker, but because structure cannot survive aggressive compression. What often differentiates one coding assistant from another is not the LLM itself, but how well the system preserves and reconstructs code context. Some engines perform better at maintaining structural detail, while others excel at understanding human intent and higher-level goals. Developers feel this tradeoff intuitively, switching between engines depending on the task. One may be better for rapid prototyping and intent discovery, while another is better for deep, detail-oriented reasoning.

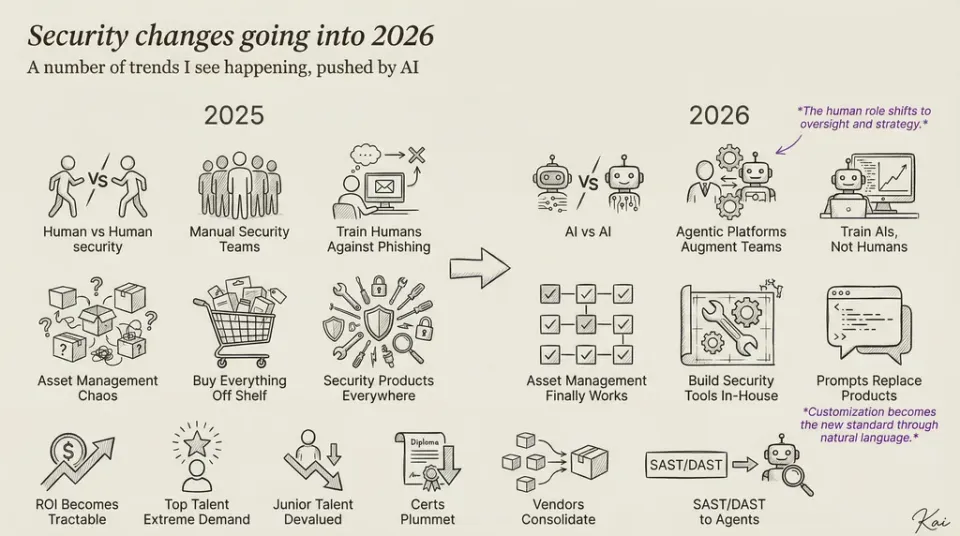

DeepSeek Changed the Western Approach

This is where the system, not the model, begins to meaningfully improve outcomes. One of the important contributions highlighted by work such as DeepSeek was a shift away from treating the LLM as the center of intelligence and toward treating it as one component in a broader process. Rather than assuming that larger models and longer prompts would automatically produce better results, the focus moved to intent and scope gating, structural normalization, and pre-model reduction. The insight was simple but powerful. Long-term knowledge lives in the model, but short-term working knowledge lives in the system that prepares each request. By reducing ambiguity, extracting trusted facts, and performing deterministic analysis before invoking the LLM, the model is given a smaller and cleaner problem to reason about. The result is not a smarter model, but a better constrained one. Shorter, more precise prompts often outperform longer ones because they reflect decisions already made by the system. Accuracy improves not because intelligence increases, but because intelligence is redistributed. Reasoning is reserved for what truly requires it, while structure, state, and validation are handled elsewhere.

Conclusion

So why does this distinction matter? Because understanding how an LLM actually works changes how you use it. When you realize the model itself is not learning or evolving during a conversation, you stop treating it like a mind and start treating it like a reasoning component. What improves over time is not the intelligence inside the model, but the way the surrounding system structures, compresses, and reintroduces information. That understanding helps explain why context drifts, why long sessions degrade, and why answers sometimes feel inconsistent. It is not because the model is confused or getting worse, but because the representation of the problem has been repeatedly reduced and reshaped. Once you see that, the behavior stops feeling mysterious and starts feeling mechanical.

This shift also changes how you work with AI. Instead of assuming the model will “figure it out” over time, you begin to guide it the way an engineer would guide any complex system. You establish structure first, then work on individual parts. You keep prompts small and precise. You understand that scope, constraints, and state must be carried explicitly, not implied. You recognize that no system can remember everything you have ever said, and that forgetting is a design choice driven by cost and practicality, not a flaw. Most importantly, you stop blaming the model for limitations that belong to the system around it. The future of effective AI does not belong to endlessly evolving models. It belongs to systems that know what to compress, what to preserve, and what to validate. The model speaks, but the system decides, and that is where real progress is happening.